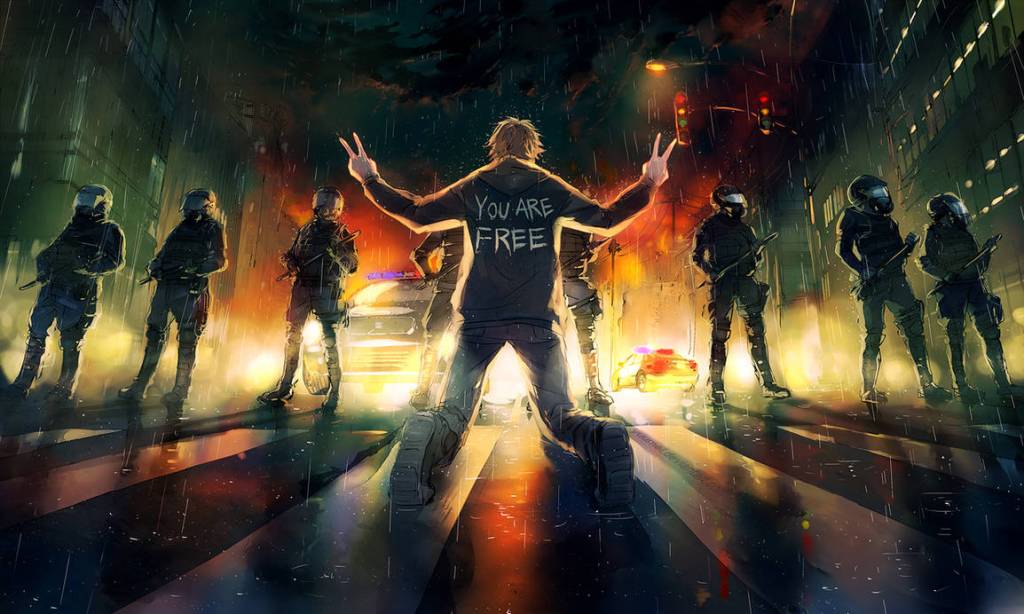

Artwork depicting the apocryphal “Ghost of Kyiv” (Credit: Antonis Kardis)

When War and Fiction Go Hand in Hand

Wartime media is always affected by the state of the world. As all art is a reflection of the society in which it’s created, art reflects the sentiments of a society towards its geopolitical rivals. Wartime media was often direct propaganda, in years past, it was far more explicit. Looney Tunes and Disney Animation produced cartoons to make America support the war. Even classic movies such as Casablanca were supporting American action in Europe against the Nazis, with Casablanca coming out in 1942, but set a year earlier, before the United States joined the war.

Media in wartime having an agenda is nothing new. And lately, it seems like we’re always at war.

Playing Off Our Fears

If you’ve watched any American movies in the last seventy years, then Russia being the bad guys comes as no surprise. Cold War hysteria made the Soviets as archetypal baddies, due to the Soviet Union being the opposing superpower, with a strong military and spies everywhere in the Western world. Despite the Soviet Union being made up of fifteen constituent republics and multiple ethnic groups, the Russian dominance of the USSR made them the stereotype, and the stereotype persisted after the fall of the Soviet Union.

During the Cold War, the 1980s marked one of the tensest periods between the United States and the Soviet Union. Ronald Reagan’s hostile rhetoric inflamed Soviet paranoia under General Secretaries Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, which resulted in renewed fears of nuclear warfare after the détente of the 1970s. The 1980s set the standard for making movies based off of those societal fears which then further inflamed said fears. The trend continues in modern media, though there are countless examples from earlier years. Some enduring examples are Top Gun and Red Dawn.

Top Gun got so much cooperation from the Navy in filming so that it would serve as a recruiting tool for the Navy, which it did. Top Gun became such a beloved movie because it portrayed the American Military as the best of the best and showed that only by working together could they overcome “The Enemy.” By focusing on the superiority of America and deemphasizing the role of its geopolitical foe, the movie became an enduring tale, which was helped by a great soundtrack and lots of footage of one of the coolest fighter planes of all time, the Grumman F-14 Tomcat (I will be accepting no arguments against how cool the Tomcat is). It never mentioned the Soviet Union by name, only calling them “The Enemy” and creating a fictional aircraft, the MiG-28 to fight against. In fact, the aircraft were portrayed by Northrop F-5s, and the USSR didn’t use even numbers for fighter designations. The sequel continued the trend by using two real aircraft: the Sukhoi Su-57 Felon and F-14 Tomcats, but both aircraft were painted with identification symbols made up for the film, and the country both were operated by was never specified. The dehumanizing the enemy is another aspect which will be discussed later, but the idea that no matter who the threat was, the US Navy could handle them was the core of the propaganda mission of the films.

Red Dawn capitalized on the fears of a communist invasion of America that were so prevalent, even if a land invasion of the United States would be horrendously impractical without Europe falling to the Soviet war machine first. It pushed people to be more patriotic, and double down on their hatred of the communists. The film itself feels disjointed at times, showing the harsh effect that fighting an invading power has on a group of teenagers who feel as though they are fighting a losing battle, and then gleefully showing those teenagers mowing down hordes of the Soviet Union’s best as if it were almost a parody. Red Dawn was, for many Americans, showing that they could fight back if the worst came to pass. Such plots were echoed in other games, with Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 in 2009 being one of the most famous examples of a Red Dawn-plot in the modern age that was executed well. The idea has cultural staying power, and that’s because of who the enemy is, and the natural fears over a foreign power hurting America.

The conflict with the USSR ending meant that most of the Russian antagonists in the 90s and 2000s were rogue operatives looking to restart the Cold War and upset the peace and budding friendship between the old adversaries. It wouldn’t be until the 2020s that Russian antagonists would return to vogue in earnest, thanks to Vladimir Putin’s interference in US elections, hostile rhetoric, and brutal invasion of Ukraine that Russians were the acceptable bad guys again.

In the 2000s and 2010s, the concerns over Middle Eastern terrorists supplanted Russia. Think of how many movies and TV shows had a generic Middle Eastern terrorist as the big bad, usually so they could get defeated by the True American Heroes.

In the post 9/11 world, where we saw the Twin Towers tumble to the ground, and the specter of terrorists cast their shadow over everything we did, and all of those movies and games that used to have us facing off against the Russians were focused on Middle Eastern terrorists/analogues to Middle East dictators.

Since much of what we saw on the screen was influenced by reality, how much of our worldview has been colored by what we consumed? Or, how much of what we consumed was created by our worldviews?

The Blurry Line between Fact and Fiction

In the early days of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the legend of a Ukrainian MiG-29 Fulcrum pilot hit the headlines. The Ghost of Kyiv allegedly shot down six Russian aircraft on the first day alone, including two top-of-the-line Russian Su-35 Flanker-Es, along with two Su-25 Frogfoots, one Su-27 Flanker, and one MiG-29 Fulcrum in the first day alone. Taking down any one of these aircraft would be a significant feather in any combat pilot’s cap. Taking down five would have made the Ghost the first European fighter ace since World War II, the first fighter ace in general since the Iran-Iraq War, as well as the first ace-in-a-day since the Indo-Pakistan war of 1965. The story went that the Ghost continued harassing the Russian Air Force for months.

The Ghost of Kyiv was a fabrication. It was a composite of multiple different action reports along with the exaggeration that comes with the game of telephone known as “wartime communication.” But it serves as a great example of how stories grow to be entertaining and blur the line between fact and fiction for morale purposes during wartime. The story exploded across social media, and people have made artwork to commemorate the Ghost’s apparent deeds. The story worked wonders for morale, and helped in the information war. It gave people a symbol to rally around while more concrete stories of real heroes were still being sorted out in the hectic miscommunication of the battlefield.

Many great war movies are based off of exaggerated accounts of real events, but we tend to overdramatize reality to make better stories. One of the reasons that the HBO miniseries, Generation Kill, based off of Evan Wright’s book of the same name isn’t more popular is that it tried to painstakingly portray the initial push of the US Invasion of Iraq in 2003. Throughout the show, there are only a few scenes where the entire company is engaged in combat. Realistic portrayals don’t resonate with audiences because we expect our movies to feel like movies. This willingness to change fact for better fiction while still telling the audience that the story is based off of real events distorts reality. People will watch the blockbuster movie that dramatizes events with attractive stars and fits neatly in a two-hour and thirty-three minute runtime, but they won’t watch the six hour documentary to make sure they understand what really happened. That’s fine, not everybody relaxes with long-form history lessons. However, they take the Gospel of Hollywood as a factual account, and that causes them to run into trouble.

The Ghost of Kyiv is an excellent example of people allowing their expectations of life as built by life influence the way they see the world. The Ghost of Kyiv became real because people wanted it to be real. Top Gun was the story of a fighter ace (by the end of the sequel at any rate) in a modern war. The idea of having a real life fighter ace in defense of their country pulls on the heart strings. Gives us something to root for. Most of your air forces working today would tell you that any single pilot having five credited air-to-air kills is almost impossible.

Why let the truth get in the way of a good story?

Life Imitates Art Imitating Life Imitating…

One of the reasons why fact vs. fiction in wartime becomes dangerous is the feel good effect. By nature, wartime propaganda wants to make sure that the audience feels that “their” side of the conflict is winning and has heroes worthy of praise. They inspire people to continue the fight, including those on the home front. As so much of society became shaped by World War II and the responses to it, that idea tended to become much more prevalent in our entertainment. Genre fiction also started becoming more prominent at that time, which meant simpler storylines, clear heroes and villains, and fantastic plots were more widely circulated in society.

As stated before, all art imitates life. Art is a reaction to the world in which it is created. So much of fiction was influenced by WWII that people began expecting those kind of behaviors from their movies. Additionally, the perpetual wartime mindset even while enjoying the peace of the Cold War pushed people to gravitate towards stories which exemplified those stories which came out of the wartime media. As those generations grew up, those wartime stories became fond memories of childhood and major creative inspirations to new creators, like George Lucas with the original Star Wars trilogy.

Society began expecting the heroes and villains to be clear like in the stories. The morality of World War II was fairly straightforward: one side was actively engaging in a genocide on a mass scale and the other was not. The Cold War was less straightforward with morality, but our stories kept telling us that ‘we’ were good, and ‘they’ were not. Dehumanizing the enemy is a crucial element of propaganda, just look at the posters showing anti-German and anti-Japanese messaging from World War II. It became second nature, and when the Soviet Union became the enemy right after the war ended, the mindset prevailed.

When the Soviet Union fell, the world was left without an enemy for a while. 9/11 was also very straightforward: terrorists rammed multiple planes into buildings, which brought the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center crumbling to the ground. United Flight 93 being recaptured by its passengers and crashed in the field in Pennsylvania gave some heroes, same with the first responders who braved the dangers of the fire and smoke and lost their lives when the towers came down. As a result, we looked for an enemy to blame, and we dehumanized them, and we went to war with a nation that had nothing to do with the attacks because they looked vaguely like the people who did.

How much of it is because we were taught to, and how much of it is because that’s what movies told us to expect?

Today in Warfare

Russia is back in vogue as the antagonists today because of their invasion of Ukraine. Despite Putin enjoying popular support across Russia, and the brutality of Russian soldiers eliciting sympathy for the Ukrainian people suffering, it’s still important to recognize that painting all of Russia with too broad a brush is a dangerous thing to do. Much like World War II, however, there can be the argument made that this is another war with clear morality. Russia broke its promises to Ukraine and engaged in a war of aggression against its neighbor. This situation does not have the complexity and moral grey areas that other wars have had in the past. That being said, while we may still enjoy movies which are unapologetic about having Russian villains, we must still give ourselves pause before falling into the old trap of believing that all conflict going on today has similarly clear-cut morality and painting one side as saint and the other as sinner without any room for nuance.

The media we consume has an effect on our worldview. Empathy for the stories we see play out is a good thing, but we must be careful not to let it completely overpower our logic and reasoning. Fiction only has as much reality as we create it to have, while the real world is nothing but reality.

Leave a comment