Berlin at night, showing the former division of the city with the types of lighting, 2013 (Credit: Astronaut Chris Hadfield)

The Cold War influenced architecture on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Berlin’s place as the front line of the conflict between East and West meant it was used by both sides to showcase the superiority of their ideology.

The Cold War was one of the most dangerous times in world history. East and West squared off against each other with enough nuclear firepower to destroy the planet many times over. It was precisely because of this that the United States and the Soviet Union did all they could to avoid direct conflict with each other in favor of proxy wars which raged across the globe, from Nicaragua to Vietnam and everywhere in between, like Angola and Afghanistan. However, since so much of their support during these wars was covert, they had to find more public ways to prove which ideology was superior to the world.

Like the stuff they built.

Threats of nuclear apocalypse and brutal neo-imperialist conflicts aside, the Cold War was a giant measuring contest between two power blocs over whose way of doing things was superior. As time would bear out, capitalism won. Communism has fallen or been moved so far away from its Marxist-Leninist roots that it barely resembles communism anymore in most of the world. But at the time, the race was still neck and neck. Showing the world over that their side was doing better came out in many different ways: art, scientific advancements, the Space Race, and architecture.

Berlin stood at the meeting point between East and West thanks to the uniqueness of its situation after the end of the Second World War. As a result, it became a showcase for East and West both to demonstrate the superiority of their side’s economic and political system. It was ground zero for spycraft during the Cold War, but also was the site of this architectural sparring match.

Cutting Slices of the Pie

Berlin was the site of the final battle of the Western Front during World War II. It was Nazi Germany’s last holdout, and they fought until Soviet forces took the entirety of the city. In the wake of the war’s end, the city was divided up into four zones of occupation: the Soviet Sector in the east, and the American, British, and French Sectors in the west. This was a smaller-scale version of the pattern of occupation drawn up for the entirety of Germany.

In the years following the war, the American, French, and British occupation zones of Germany became the Federal Republic of Germany, or West Germany, with its capital in the city of Bonn. This is the German government that still exists today. Troops were stationed in the country from the western forces as a deterrent against Soviet aggression, but West Germany was its own nation. Similarly, the Soviet occupation zone of Germany became the German Democratic Republic, and the Soviet occupied zone of Berlin became East Berlin, the capital of East Germany. The western governments didn’t recognize East Germany as a nation for many years, nor East Berlin’s authority as capital, but this was more of an international relations question rather than an administrative question.

The end result was the same: the allied-occupied West Berlin was fully encircled by communist territory. West Berlin was never officially part of West Germany, but it was treated as such. Thus, West Berlin was a great way to give the Eastern Bloc front row seats to the capabilities of capitalism. The West did not let that chance go to waste.

Dateline: West Berlin

One of the most impressive West Berlin landmarks was the first thing many international travelers would see when they arrived in West Berlin, and it pre-dated World War II. Berlin Tempelhof Airport was the main airport in the German capital between its reconstruction in the 1930s until Tegel took over by the 1970s. Imposing and stoic with a certain elegance, Tempelhof is an iconic historic landmark of Berlin, which the city doesn’t know quite what to do with. The runways are out of use, but still exist as a city park, which Berlin residents have voted to keep instead of opening the land up for redevelopment. For the moment, it seems that’s what Tempelhof will remain. Despite being built before the Cold War, Tempelhof’s still an iconic image of the great struggle between East and West due to its status as the central location for the Berlin Airlift, when Stalin ordered the land routes to West Berlin blockaded, forcing the Western Allies flew supplies into the city for almost a year before Stalin relented. This act was a symbolic gesture to begin the Cold War in earnest and bought West Berlin its right to exist and be the showcase for the West during the Cold War.

Tempelhof’s successor, Tegel Airport, became iconic in its own right because of its interesting design, and its status as one of Berlin’s two airports after Tempelhof closed in 2008. Originally constructed as a French airfield to help with the Berlin Airlift, Tegel became a passenger airport when commercial airplanes got too large for Tempelhof’s relatively short runways. The iconic hexagonal structure was built in the 1970s and far outlasted its intended purpose, finally closing in 2020 with the completion of the long overdue Brandenberg Airport.

Part of the reason Tegel became so iconic was the same reason Tempelhof did: it was the first thing many people saw when they entered the city. The other part was that it was innovative. This was an airport with decentralized check-in, which meant you checked in for your flight right near your gate. It meant less time spent traveling through the airport, less time spent waiting in lines, and a smoother experience. However, as the designers noted, the modern security needs due to terrorism have made such a design outdated. The airport was built for roughly two million passengers a year with the potential to handle five in the future. In 2019, a year before its closure, Tegel saw over 24 million passengers. Today, Tegel is currently being redeveloped as a tech and community center, keeping its iconic terminal building and tower intact. In the meantime, it’s playing host to techno clubs and other cultural events.

Airports aren’t the only cool things West Berlin held. Possibly the most interesting conference center in the world sits, unused, in Berlin today, undergoing renovations and looking for future use. The Internationales Congress Centrum (ICC) Berlin has been affectionately called the “Spaceship.” The futuristic structure was opened in 1979 as a kind of response to a similar building in the East. The building has a futuristic feel to it and is a complex but easily navigable space which packs a lot into a relatively small profile. It represents the best of retrofuturism, with a lighting setup throughout the complex inspired by human anatomy, and several rooms that wouldn’t look out of place in science fiction movies made in the late 70s or early 80s. Its distinctive orange tunnels below have shown up in several movies, as has much of the rest of the complex. Closed since 2014, the building is currently undergoing asbestos removal, which does spend money, but also buys time for those in charge to figure out what to do with it.

The Tiergarten was one of the areas devastated by the Battle of Berlin. After the city was divvied up, the park found itself firmly in West Berlin. Perhaps less an example of architecture and more of city planning, the presence of such a large park (it was the biggest in Berlin until the closure of Tempelhof and its transformation into a park) within the city was seen as a necessary feature of West Berlin. Perhaps one of the most significant contribution’s to Berlin’s architecture was the Interbau 1957 Expo held near the Tiergarten. With the West prioritizing connection with the rest of the world, and the passage of free trade, West Berlin’s status as a world-important city was bolstered by inviting international architecture to be shown off so soon after the end of World War II. This would signify the number of foreign architects developing designs which would be erected in West Berlin in the years to follow.

The Kurfürstendamm, or Ku’Damm for short, was the central shopping area of West Berlin during the city’s divided years. It was rebuilt for commerce, not necessarily beauty, but nevertheless became an important organizing place for student protests and the like. It became one of the social centers of West Berlin with night clubs and fancy stores. Most of its original architecture was lost during World War II, and the reconstruction never quite recaptured its original glory. While it is still a popular destination after the reunification of the city, it never quite saw the popularity of the Alexanderplatz which was firmly in the East, or Potsdamer Platz, which was at the heart of the divided city and has today become a bustling public square, and fully representative of the renewal brought by German reunification.

West Berlin was a hub for the arts and commerce, but many of Berlin’s modern famous landmarks were originally built on the other side of the Berlin Wall.

Dateline: East Berlin

Upon German reunification in 1990, the new German state took great pains to preserve some memories of its communist past. The government of East Germany was dissolved, and the East German states were incorporated into the government of West Germany, but the reunified state was aware of its position as a custodian of history. In a nation already sensitive to its history as the center of the Nazi Reich, the stories of the German Democratic Republic were similarly important to preserve. More importantly, East Germany was home to plenty of Germans now living in a reunited nation too, which meant that they deserved a fair amount of memory towards their childhoods as much as the West Germans did. Being the venue at the center of the Cold War, Berlin has a great deal of places still standing as memorials to its communist past.

Ironically, many of modern Berlin’s iconic landmarks were on the eastern side of the Berlin Wall during the Cold War. With the proximity of East Germany to the Western Allies, and the close view which westerners could get of the Eastern Bloc from West Berlin, East Berlin had the honor and pressure of showing the triumphs of communism for all to see. The East Germans and their Soviet benefactors took that role seriously.

The Alexanderplatz (Translation: Alexander Square) is a public square in the Mitte district of Berlin named for Tsar Alexander I who ruled the Russian Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. Devastated by the bombing campaigns of the Second World War, the East German government opted to rebuild the Alexanderplatz into a pedestrian zone, allowing it to become a meeting place for East Berliners. It would become the site of the largest anti-government demonstration in East Berlin’s history on November 4th, 1989. Five days later, the Berlin Wall would fall, and with it, East Germany as a whole.

Of course, the two large landmarks most associated with the Alexanderplatz and thus East Berlin are The World Clock and the TV Tower. The World Clock became the central meeting point in the Alexanderplatz. This was a remarkable invention which showed East Berliners the time in every time zone across the world. Places they were not allowed to travel to magically had a slight bit of the mystery pulled away from them. It would be the gathering place for the aforementioned demonstration on November 4th, 1989. The TV Tower is not directly located in the Alexanderplatz, but stands as the tallest structure in Germany a short distance away. Built both as an active TV and radio broadcast tower, and a symbol of communist supremacy, the tower remains a landmark symbol of Berlin today. There is an observation deck that allows visitors to catch a view of Berlin from on high, and the TV Tower remains one of the most popular tourist destinations in the city.

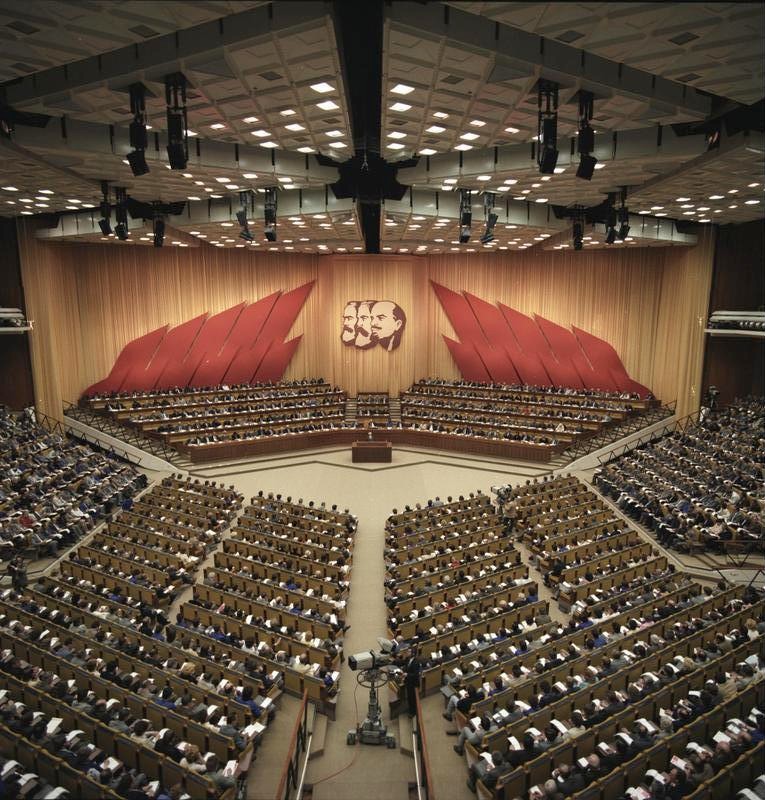

Not everything the East German government built remains intact, however. By the 1970s, it was decided that the East German parliament, the Volkskammer, needed a new meeting place. The Palace of the Republic (Palast der Republik) was designed as a government meeting house, but also as a palace of culture for the people. The Palace of the Republic was built on the site of the Berlin Palace, the historical home of the Hohenzollern Kings of Prussia, and later that of the Kaisers when the German Empire was founded in 1871. After being damaged by allied bombing in World War II, the Berlin Palace was torn down by the communist government in 1950, and the Palace of the Republic was built in its place, opening in 1976. It was seen, again, as a triumph of communism to construct a palace for the people on the site of the home representing Germany’s militaristic and imperial past. The building was nicknamed “Erich’s Lamp Shop” after the longtime leader of East Germany, Erich Honecker, and the distinctive light fixtures in its atrium. Honecker built the Palace of the Republic to be a place for its citizens as well as their government, with the building hosting three restaurants, a bowling alley, a movie theater, a concert hall, and several shops. Its Great Hall was able to be rearranged (relevant section starts at 21:14), so that the room could hold concerts, galas, and other events when not serving as the meeting place for the Volkskammer. The Palace of the Republic fell into disuse in 1990, with the reunification of Germany, and would be shuttered and stripped due to asbestos. The controversial decision was made by the German parliament in 2003 to tear down the building and rebuild the Berlin Palace on its grounds. The reconstructed Berlin Palace was completed in 2020, and now houses the Humboldt Forum museum.

The Karl-Marx-Allee is an excellent sight for some of the more normal architecture of the East. Much of the area is made up of pleasant, but simple apartment blocks, not unlike the style common within the Soviet Union and other areas of the Eastern Bloc throughout its time under communism. It exists as one of the largest areas of communist architecture in good condition. The area is mostly residential, with large apartment buildings, but remains noteworthy nonetheless.

Finally, no discussion of Cold War architecture could be complete without mention of The Brandenburg Gate, which is another iconic Berlin landmark which predated the Cold War. Finished in 1791, the triumphant arch was ordered by King Frederick William II of Prussia to commemorate military victories and mark the historical start of the road to Berlin. The Brandenberg Gate was firmly in East Berlin and was cut off from West Berliners when the Berlin Wall was constructed in 1961. Shots from the west of the Wall in the foreground with the Brandenberg Gate towering over it in the background became a common image of the divided city. This view was seen in a great number of photographs and provided the backdrop for President Ronald Reagan’s famous speech in 1987 when he demanded, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” The Berlin Wall would fall in 1989, and with it, the East German government.

East vs. West

With West Berlin being associated with West Germany, and the Allies, its position kept much of its post-war architecture close to that of the rest of the Western world. Many of the restrictions or ideological handicaps of communism did not exist in the west, therefore buildings in London, New York, and Paris were also common to West Germany in many aspects.

In contrast, East Berlin had the auspices of communism to uphold. Influenced by the Soviet Union, which changed its own architectural priorities over the years, the East German government sought to show the West and the world that communism was superior throughout their culture, including with their buildings.

Berlin was the center of the Cold War in many ways. Nicknamed the “City of Spies” and close enough for capitalists and communists to pick up each other’s television signals at the very least, Berlin was a meeting point of ideologies in a way few other places during the Cold War could claim. The end result of this struggle is a city which combines the styles of both sides. Since reunification, Berlin has taken pains to reconcile its history and the differing growth of the city when it was torn asunder. In the years since reunification, Berlin has taken to expanding and continuing its architectural styles. The end result is one city with a period of two histories, and is now seeking to add to its already impressive architectural history with new creations that exemplify the modern Germany, now multiple with generations on from reunification. For example, Postdamer Platz was devastated during the Second World War and never rebuilt as it was part of the no man’s land in between both halves of the Berlin Wall. After reunification, the square became a hub for modern development, a symbol of Germany’s and Berlin’s renewal after the end of the Cold War.

Berlin, while influenced by the great benefactors: the USA in the West and the USSR in the East, still maintained a feeling of being distinctly German. The architectural stylings of America and the Soviet Union had much larger differences. Their styles were driven by society, need, ambition, or a combination thereof.

West Berlin Image Credits

Tempelhof: K.H. Reichert

Tegel Airports: Wikimedia Commons

ICC Hallway: Slow Travel Berlin

ICC Subway Tunnels: Chris Chabot

Victory Column in Tiergarten: Visit Berlin

Kurfürstendamm and Leibnizstraße: Wikimedia Commons

East Berlin Image Credits

Alexanderplatz Demonstration: Wikimedia Commons

Alexanderplatz World Clock: Fabio Casadei

Alexanderplatz TV Tower: Hans van Reenen

Palace of the Republic Exterior: Wikimedia Commons

Palace of the Republic Great Hall: Wikimedia Commons

Karl-Marx-Allee: Berlins Taiga

Berlin Wall and Brandenberg Gate: Wikimedia Commons

Leave a comment