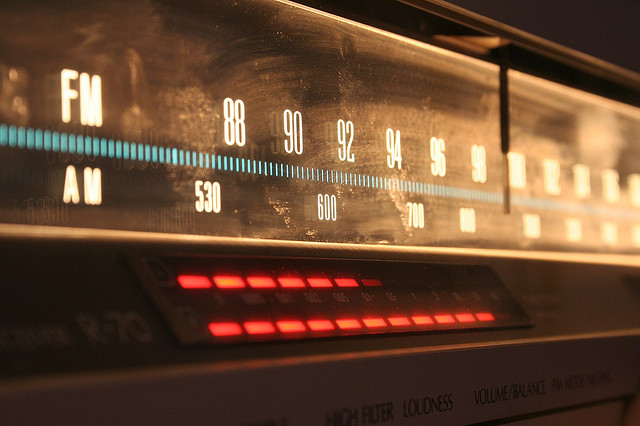

Authority of Radio Stations (Credit: jlaytarts2090)

Radio is a technology long on decline, but never quite dead.

In the lead-up to Thanksgiving last week, the infamous clip from the television show WKRP in Cincinnati about the disastrous and hysterical fallout from the fictitious station’s poorly-devised Thanksgiving giveaway made the rounds again. While the clip retains its humor, some of the cultural relevance has seemingly faded. With the rise of the internet and the ease of communications, the regional appeal of radio stations has fallen off. With the social media platforms responsible for sharing music in today’s world being controlled by algorithms, the idea of humans working to curate a selection of music is seen as unprofitable and obsolete, especially for such limited returns.

Truth is, radio stations are struggling, but they’re not quite dying either.

The Voice of a Generation

On their 1980 studio album, Permanent Waves, Canadian progressive-rock band Rush wrote a song titled “The Spirit of Radio.” The song was a hail to the disappearing free-form format FM stations which were being replaced by more commercially minded outlets. It describes the radio as a free frontier all its own, a technological marvel meant for bringing people together.

Radio had its origins as a technology in the late 1800s but didn’t start becoming common in American households until the 1930s. Radio sets became cheaper, and a large number of households had one by the end of the decade. Radios became standard in new cars and were available in public places. Most households in America still relied on radios during and following World War II. As more households were able to afford televisions after the war, entertainment and news infrastructure pivoted towards this new market.

Radio stations across the nation became havens for rock music in the post-war world. With television on the rise in the 1950s and 1960s, radio stations were forced into stronger and stronger competitions to be profitable. At the time, radio was the dominant form for access to music. Record labels had pull over what got played, and while the disc jockeys still answered to station leadership, everybody in the industry still knew what the end goal was: to make money. Stations could play a little loose with the rules and expectations of radio so long as they brought in listeners and advertising dollars. More than that, rock music was the dominant style of the time. Stations who could find something to set themselves apart could make everybody happy.

Rock stations helped stoke the anti-establishment sentiment on the rise in the 1960s. With the Vietnam War in full swing, and Americans dying every day, much of the music being written at the time was critical of war, strife, inequality, racism, sexism, and uncaring or corrupt leadership. As with many things related on the arts, many rock DJs of the era were left-leaning and sympathetic to or participants in the peace movement which was a response to Cold War tensions and the carnage of Vietnam. Student protest groups were one of the largest demographics in opposition to the war, and many universities had radio stations run by those students.

The Vietnam War inspired a great deal of anti-war music, like most wars do. One of the big differences with Vietnam compared to previous conflicts was that the soldiers in the field got access to music because of radio and other avenues. However, listening in such a way was a more communal experience than it is today. Everyone listened to music, but everyone listened to the same music. In turn, this created strong positive associations and created a demographic which gravitated towards the same music on their return home. Think about the average person serving in Vietnam: young men at the tail end of their formative years who were ordered to be there by the federal government against their wishes. The peace movement of the 1960s, culminating in Woodstock, was an explicit rejection of the culture which led to the Vietnam War. This culture, in turn, was represented by the anti-war music which would become so very popular on radio stations.

Once the soldiers returned home, they found many people in the radio business agreed with their own resentment of the war. The DJs, both professional and student alike, showed the power of radio. This was a technology which could connect people and create an instant community. More than that, it could wield immense influence. Vietnam ended because the nightly news on television showed the films of combat and brought the war home to millions of Americans. However, it was on the radio that people

No discussion of radio would be complete without mention of Alison Steele. Steele was one of four women hired by WNEW in New York City upon its launch in 1966 to create the nation’s first all-women disc jockey crew. She became one of the first women DJs in the country and was the only one who stayed when WNEW transitioned to a progressive rock format by the end of 1967. January 1st, 1968, saw Steele take on the timeslot, format, and persona which would cement her into a radio legend. Under her nickname, “The Nightbird,” Steele anchored her show from 2-6 AM, and heavily favored progressive rock. If the music programming wasn’t enough to set her apart, the other aspects of the Nightbird would. Steele was unscripted, blending a playlist which was made and changed on the spot with mysticism, poetry, and the thoughts of listeners who called in as she gave them something to hold onto in the middle of the night.

Alison Steele helped make overnight radio a popular format. She was an early example of the power that a specific DJ could have to bring listeners to a specific show and a specific station. Studio owners loved this because it meant large, consistent audiences to help with financial projections easier. However, it also meant that the days of radio as a free frontier for music were limited.

While radio’s time as an avenue for free artistic expression would hit its peak in the 1960s, the attitude would follow well into the 1970s and over into the 1980s to an extent before culture saw another great shift and led to radio’s modern state.

The 1990s and Decline

The 1980s into the 1990s would see two major changes in radio’s history. The adoption of cassette and CD players made home media easier to afford and take up less space than vinyl records and record players of days past. People could curate vast collections of music for listening at home, on-demand.

The other major change occurred midway through the 1990s, courtesy of the United States Congress. Radio stations used to be much more community affairs. Local stations were owned by local ownership, spoke to local tastes, and covered local issues. They were the voices of their communities. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 changed everything by removing limits on station ownership. Where one organization could not own more than two stations within a given market, after 1996, they could own as many as they like. Additionally, an entity was now allowed to own television stations and radio stations at the same time.

To equate it to more current events of a comparable measure which have been in the headlines, this situation has parallels with Sinclair Broadcast Group. Sinclair is the largest owner of local television stations across the nation. It has been accused of preparing stories for all of its channels to run in an effort to influence viewers. The editorial teams of local news channels are now beholden to talk about stories which may not have a direct effect on their communities. Thus, it dilutes the impact and importance that these stations have to their local communities, and they speak more to corporate concerns rather than local issues.

In a precursor to Sinclair’s stranglehold over the local television networks, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 essentially killed local radio. After its passing, media conglomerates bought up local radio stations all over the country and robbed those local stations of their local significance. Format, programming, playlists, and personnel were decided by national organizations attempting to maximize their return on investments.

Cassettes, CDs, and digital files brought music into the home and on the go in ways that radio could not quite hope to match. Radio stations adapted to survive the great change.

Chatter on the Airwaves

As a result of the decline in the 1990s, many stations began shifting to a talk radio format. Talk radio had its origins in radio’s early days in the 1920s and 30s. Much of the early adopters of the format were inspired by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Fireside Chats. Roosevelt showed the immense reach of radio to ordinary Americans. As radio grew in popularity, more AM stations focusing on music cropped up. However, with the switch from AM to FM allowing most music format stations to broadcast in greater quality, many AM stations switched formats in an attempt to find something to air and retain listeners leading to the prominence of the talk radio format.

Part of the rise of talk radio can be attributed to the disc jockeys. As radio stations necessitated something more than just their programming to attract listeners, and advertising dollars, eccentric hosts gained more popularity. Some of them, such as Howard Stern, became more famous for their own broadcasting rather than the musical programming of their shows. Edgy humor, pop culture topics, and loud personalities ended up defining the shock jock as a type of radio personality.

Talk radio shifted into the political sphere. Base model cars had AM radios in them as standard, and radio sets were cheap, so radio was very accessible. News, sports, and music all came from them, and with talk radio formats becoming more popular, political personalities could find homes on the airwaves. The Fairness Doctrine required that controversial issues with significance to the public were presented in a manner that was, “honest, equitable and balanced.” In the wake of its repeal in the 1980s, partisan political radio became acceptable under FCC guidelines, and the format took off at supersonic speeds.

The reason talk radio took off is because people would turn in for personalities that they found entertaining or insightful to listen to. Howard Stern built a media empire by being an engaging personality people wanted to listen to. As time wore on, and radio became less of the preeminent way to interact with music, talk radio became a bandage for a gaping wound which threatened radio as an industry.

Of course, one of the biggest threats to radio had been around since the early 80s, and it’s only gotten more intense.

Radio on the TV…and then the Internet

Another mark of the declining radio entertainment industry was a little channel called Music Television. When MTV started broadcasting in 1981, it kicked off its run with the music video for the song “Video Kiled the Radio Star” by The Buggles. The idea of pre-recorded, pre-produced music videos for songs had existed before, but MTV’s existence marked a focus shift away from the live-performance-based formats of music television in decades past. In the 1980s, more artists would make music videos for their songs in hopes of receiving airtime on MTV, which helped introduce their music if the radio stations would not pick it up. Radio was still a more regional affair while MTV was broadcast nationwide, before eventually going global.

MTV would end up supplanted by the internet. Music videos would debut on YouTube by the 2010s as artists and record labels found that legacy media couldn’t keep up with the internet. Instead of waiting by the television through a block of music videos to see the one they wished, viewers could search for the specific video and watch it as many times as they wished on their schedule, not the programming directors’. Record executives liked this because it meant they stood to make more money. The advertisers would be tied to the specific videos, not only meaning that MTV’s cut was reduced, but the more repeat viewings a particular video received, the better metrics on popularity of a particular song were available. This in turn translated it to higher costs for licensing popular songs. While it was not the sole determining factor, the focus on artists – or more accurately, their management – maintaining control over the music videos helped provide metrics useful in a business sense to the music industry.

As a result, MTV pivoted away from music programming to reality television in the 2000s in an attempt to remain profitable. The efforts would be in vain, as MTV announced that they will be shuttering almost all of their television channels at the end of 2025, including the channels which broadcast music videos. Video killed the radio star, and then the internet killed the video star. Social media has become the new battleground for attention and fame. Radio stations have been mostly supplanted by streaming services. An on-demand of massive proportions curated to fit each listener’s tastes is one incredible selling point.

However, sometimes, algorithms aren’t the desired end solution.

Still Coming to you Live

Everything old is new again. Nostalgia operates in cycles, and people are trying to find new things for today which had their supposed day in the sun. Vinyl records were killed by cassette tapes, which were killed by CDs which were killed by MP3 players which were killed by streaming services. Film cameras were killed by digital cameras which were killed (to a degree) by cell phone cameras. Yet people are buying vinyl records now in greater numbers than the 1990s and 2000s. Film cameras have made a comeback with dedicated photographers who prefer the restrictions of the medium. So too does radio yet live.

College radio is making a comeback. With operations being wholly or partially subsidized by the university, there are scores of local radio stations operating today which are seeing a resurgence in both staff and in listenership. They make up the largest portion of non-religious, independently operated radio stations still in existence in America today. College radio is a haven away from the corporate conglomerates which took over radio stations after 1996 and is one of the last bastions of the community which radio built in its heyday.

No algorithm can curate a mix the way a human can. The inherent emotional unpredictability means that a human can find songs that feel right when fit together despite gigabytes of metrics saying they shouldn’t. Even iHeartMedia, the largest owner of radio stations nationwide, recently announced a new policy banning AI-created music, podcast content, or on-air personalities.

Radio is one of the unsung equalizers, a cheap and accessible way to share music and entertainment. It’s place in modern society is in the merge of machine and man, technology requiring the guidance only a human soul can give to carry its songs over the airwaves and into our hearts.

Leave a comment