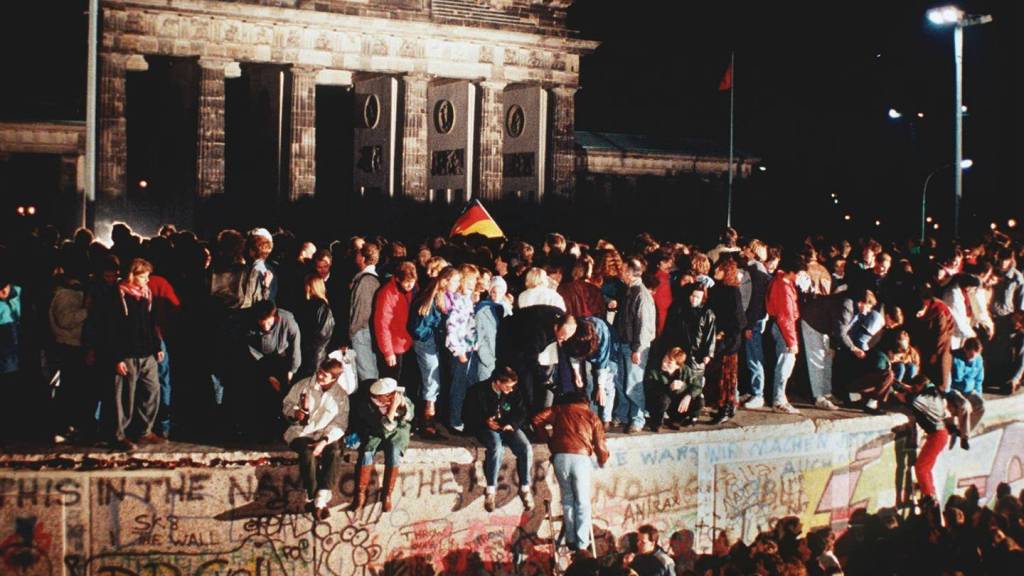

The Fall of the Berlin Wall, November 1989 (Credit: Johns Hopkins)

The Fall of Communism was a complex chain of events which set the stage for the world today.

I grew up in the shadow of the grave of the Cold War, and the shadow of the smoke at Ground Zero. My whole life has been marked by conflict and division. So much of the pain and bloodshed today can be traced back to the Cold War and its end. It’s an era I was never taught about in school, and I’ve had to learn for myself in recent years to make sure I’m speaking about events with a measure of knowledge. It helps in the voting booth.

I was never taught to understand the most fundamental shift of the world order since the World Wars in school while growing up. Events just a few years from before I was born remained shrouded in mystery, and so did the questions those events spawned. I was always just taught that Russia just has great enmity for the West. That the reason the Middle East is so volatile is that those people have been fighting for those piles of sand for thousands of years. So many of these questions are answered in the same throwaway manner.

Throwaway statements don’t do much to help one understand the screaming or the bloodshed. Without understanding it, it cannot be stopped. So much of the state of the world we live in today is the legacy of decisions made by our parents and grandparents during their years at the helm. Without teaching kids what happened in the world before them, they don’t stand a chance at making their mark on history once it becomes their turn to lead. The argument that “we can’t teach recent history because it’s too politically charged” is a bald-faced lie. World affairs fall beyond petty politics.

The troubles remaining hidden by the shadows of ignorance only mean the damage they cause remains unseen until it is too late.

Openness and Restructuring

In 1985, the Soviet Union was struggling with leadership. The Soviet military had been taking heavy losses with nothing to show for six years in Afghanistan, the economy was stagnating, and there were fears in the upper levels of the Soviet government of a NATO first strike. In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev succeeded Konstantin Chernenko, Soviet leader for the previous thirteen months. Chernenko was preceded by Yuri Andropov, former head of the KGB and General Secretary of the Communist Party for the fourteen months before Chernenko. Both of these men suffered from ill health and spent most of their time as leader of the Soviet Union in the hospital. Andropov’s predecessor, Leonid Brezhnev, had also suffered from ill health for years by the time his eighteen year tenure as General Secretary ended with his death in 1982.

Mikhail Gorbachev’s ascension was an effort by the Soviet Politburo to give a young star within the Central Committee the authority needed to give the Soviet Union hope for a renewed future. Gorbachev was a bit of an idealist. He believed that the Soviet Union could survive and become great once more. Gorbachev was also a realist and realized that a seismic shift of Soviet society needed to occur in order to save the Soviet Union. It was this line of thinking that led to a number of reforms which exposed the weakness of the Soviet Union and brought the Iron Curtain, European Communism, and the Cold War to their ends.

Gorbachev was, at his heart, a reformer. The policies of glasnost and perestroika are familiar to those who have taken a world history course in high school, but their reasoning and importance probably still elude most people. The words mean “openness” and “restructuring.” The former refers to the relaxed state controls over free speech and the media, while the latter refers to the economic changeover to a less centrally planned economy.

Dating back to the days of Lenin, which were the earliest years of the USSR, there was a definite restriction on what people could say or think. This only got worse once Stalin took the reins of power in 1924 and held onto until 1953. Stalin, more than Lenin, was responsible for the culture of the Soviet Union, and part of that was absolutely no criticism of the government allowed. People would rarely speak even the mildest criticism for fear of the secret police dragging them away in the middle of the night. Said secret police carried many names over this years as it evolved into the more widely known KGB, but its methods were frighteningly consistent. A Soviet joke retold by President Reagan highlights the stark difference between the US and USSR in terms of free speech. Gorbachev’s willingness to allow open criticism of the government of the Soviet Union was beyond the wildest dreams of many Soviet Citizens. It meant they could speak their mind and be informed in ways they previously could not have. It also made the idea of economic cooperation with the great enemies of the Soviet Union a little bit more palatable.

The importance of perestroika was that the USSR was running out of money. It doesn’t take a stretch of the imagination to believe that Gorbachev’s eagerness to engage in arms limitation treaties with the United States was as much a humanitarian desire as it was an economic one. Nuclear weapons and their delivery systems are expensive to produce and maintain. Gorbachev could cut Soviet bills without falling behind if the USSR and USA both agreed not to build so many nukes. By 1987, the Soviet Union was struggling hard with feeding its population, all the while financing the War in Afghanistan since 1979, and cleaning up the Chernobyl Disaster of April, 1986. This also meant that an influx of cash from the West would help keep people fed and permit the Soviet Union to remain intact.

The need for economic ties with the West forced the USSR to create stronger cultural ties as well. Glasnost meant that the government would be more openly accountable to its people, but also that the people could read, watch, and listen to media they were previously prevented from seeing. Reality, not the carefully cultivated experience okayed by the most senior officials in Moscow, was finally in the grasp of the Soviet citizens.

Chernobyl was the first outing for Gorbachev’s policy of openness, having Soviet state media admit to managerial incompetence. It was a shock to the USSR and the world. To paraphrase HBO’s 2019 miniseries, Chernobyl, which depicts the Chernobyl incident, it “humiliated a nation obsessed with not being humiliated.” It would lead further down the road of openness and building closer ties with the free world when Western music acts were invited to play in the Soviet Union. Billy Joel was one of the first, documenting his 1987 stops in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) on the live album Kontsert (rereleased in expanded form as A Matter of Trust: The Bridge to Russia). Music captured the feelings of hopefulness like few other forms of media did. The Scorpions released the anthem for the end of the Cold War in 1990 on their album Crazy World. Inspired by their time in the Soviet Union when playing at the Moscow Music Peace Festival on August 13th, 1989, the band used the sense of hope and unity in the air to inspire the song Wind of Change.

In the Soviet Union itself, there was a sense of East meeting West in earnest for the first time in generations. Not since the days of Imperial Russia would the territories have such a close relationship with their neighbors to the west.

In the rest of the Eastern Bloc, the citizens could only look on with envy as their governments remained committed to a more old school approach. Of course, when freedom is denied, it shall be taken with great intensity and in greater extremity than anticipated.

When the rest of the communist world was denied basic freedoms, they decided that they were done with communism.

The Autumn of Nations

Gorbachev’s reforms within the Soviet Union were viewed with awe and hope in the other countries in the Eastern Bloc. However, this hope was soon short lived as many of their own governments refused to implement favorable terms. The people took to the streets on a massive scale not seen behind the Iron Curtain before and demonstrated for free elections. Many of the countries in the Eastern Bloc did end up holding elections, where the various communist parties lost, and willingly gave up power over the course of the second half of 1989. Romania was the only real exception and remained the last of the Eastern Bloc nations to move away from their longtime communist governments because Nicolae Ceaușescu refused to give up power. He was overthrown in a violent revolution. While most of the leaders of ex-communist countries lived out their days in the nations they previously ran or in exile, Ceaușescu and his wife were executed on Christmas Day in 1989, bringing the otherwise peaceful Autumn of Nations to a harsh but definitive end.

Perhaps the most symbolic turnover came in the German Democratic Republic. Erich Honecker, the longtime head of East Germany’s government, was a staunch hardliner, and resisted Gorbachev’s progressive reforms. He was forced out of power by the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) on October 18th, 1989, and replaced with Egon Krenz. Krenz would later resign on December 3rd when the government of East Germany collapsed in the wake of the Berlin Wall coming down on November 9th.

The Berlin Wall coming down was something that both sides thought would never happen. It was a landmark moment in history. The Wall had been a symbol of division between East and West since its erection in 1961. It signified the Cold War in a way few other things had. John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan both gave famous speeches in front of it on the West Berlin side. It had stood for some people’s entire lives by the time the Cold War ended. The Berlin Wall, the image of a divided Berlin, and the mystery and oppression behind it were something that most people believed would always be there. Peter Jennings reporting live at the scene the next day as Berliners chiseled away at the concrete and lighting off fireworks and drinking champagne was nothing short of a miraculous television broadcast.

The irony about the Berlin Wall’s collapse, which snowballed into the end of the East German state, is that it happened completely by accident. Leading up to the fall of the wall, East German citizens were leaving the country in droves by the borders with Hungary and Czechoslovakia (now Slovakia and the Czech Republic) which were not being enforced. As a result, the East German government decided to allow their citizens to leave once they received a visa from police stations or other government agencies. However, the crucial mistake happened when this was announced at a press conference led by a Politburo member, Günter Schabowski. The issue with Schabowski’s address is that he explained that people could leave the country through all border checkpoints with West Germany, and that it would go into effect “without delay.” The meaning was that people could apply for the visas immediately. The understanding was that East German citizens could just up and leave, which they did. As throngs of East Berliners descended upon border checkpoints with West Berlin, the GDR’s border police refused to open fire to keep the crowds back, eventually deciding just to open the gates. The rapid meeting of Easterners and Westerners set the stage for a rapid vote on reunification. East Germany held their first free elections in its forty year existence in the early days of 1990. The SED was trounced, and German reunification, another Cold War pipe dream, was the primary mandate of the new government. Work began immediately, and the full treaty of reunification went into place on October 3rd, 1990.

For the most part, the revolutions of 1989 led to better situations for the citizens of these countries. New ties could open with the west, and new governments had to find solutions to new problems which cropped up in the aftermath of ditching centrally planned economies. It was the right of self-determination that made it so attractive to people, and the Eastern Bloc nations, which helped prop up the Soviet Economy, now had the chance to use their own resources for their own gain.

Gorbachev understood the need for the Soviet Union to allow events to play out without intervening. Weary of the imperialism practiced by the USSR for his whole life, and aware that the movement towards the West would only be strengthened by further oppression from Moscow, Gorbachev instituted the Sinatra Doctrine – named in allusion to the Frank Sinatra song “My Way” – for the other nations in the Eastern Bloc. As a result, Moscow did not intervene while communism was overthrown.

Not everyone was so happy that the Soviet Empire had lost its empire.

The Wind of Change

At the time, many members of the Soviet Union and the other Eastern Bloc nations resented Gorbachev for his hands-off approach. Hardliners in the USSR saw it as the ultimate betrayal of the Soviet Union’s work over the previous decades. The citizens facilitating revolutions in the communist bloc saw it as an abandonment of his desire for progressive reforms and giving the people a legitimate voice in their leadership. Gorbachev destroyed the Soviet Union by trying to save it, but perhaps the USSR was beyond saving in the first place, supported by a foundation which had rotted for years under Brezhnev with no help in sight. The Soviet Union had created a new aristocracy through political dealings and machinations of party members, and Gorbachev felt that he, as steward of Soviet communism, had a responsibility to give the state power back to the people from which the USSR originally derived that power.

Gorbachev’s reforms started the ball rolling to end the Cold War, but he didn’t realize he would be unable to stop it. Reform was necessary, but perhaps it came too late. Once the people tasted of freedom, it would be an elixir they would not just walk away from. Many of the constituent Soviet republics who had previously desired independence when the Russian Empire was falling down, like the Baltic states, reasserted their right to independence.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union is a complex story in and of itself. It was the result of decades of enmity and hostility, of repression and economic stagnation. The short version is that, as Soviet society became more open thanks to Gorbachev’s reforms, they could see as the rest of the communist world rejected communism, a centrally planned society, and the political repression which came with it. The people yearned to have a voice in their leadership. Gorbachev was less enthusiastic about the breakup of the Soviet Union, and the Sinatra Doctrine only went as far as applying outside the borders of the Soviet Union itself. Once a train gets rolling, however, there is little that can be done to stop it.

Gorbachev initially had gotten many member states to agree to the New Union Treaty, which would have kept the USSR together as the Union of Soviet Sovereign Republics (Gorbachev wanted to preserve the widely used acronym). Under the New Union Treaty, the entire political system would be replaced to give the constituent republics more autonomy and more power on the local level, while still reporting to Moscow and having common diplomatic and military efforts. It was an attempt at the best of both worlds. Russia, Byelorussia (Belarus), Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kirghizia, Tajikistan, Turkmenia, and Uzbekistan all helped draft this proposed treaty and their citizens overwhelmingly supported it in the referendum. Meanwhile, Armenia, Georgia, Moldova, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania all pushed for full independence and refused to take part in drafting the treaty. It wasn’t even a consideration.

Ultimately, it didn’t matter. The treaty never went into effect. In August 1991, members of the KGB conspired with conservative officials to attempt a coup d’etat attempt against Gorbachev. Boris Yeltsin, the President of the Russian Federative Soviet Socialist Republic, supported Gorbachev and helped push the conflict towards an expeditious end. Yeltsin would then use his increased influence to whittle away at Gorbachev’s authority and set himself up as the leader of the new Russia when the old Soviet bear finally keeled over.

The remaining republics, led by Yeltsin’s Russia, no longer had confidence in the Soviet Union. Yeltsin maneuvered to have the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics dissolve from out underneath Gorbachev. A President without a nation and the leader of a government with nothing to govern, Gorbachev had no choice but to accept the new order of things. The President of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev resigned on Christmas Day 1991, and the next day, the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union’s upper house, the Soviet of the Republics, voted the Soviet Union out of existence.

The Shadows Ahead

With all said and done, the West won the Cold War. Overwhelmingly, the sentiment was that the age of conflict was over for good. It was a widely held belief that liberal democracy had won and shown the world its peaceful and productive nature. The conflicts of the 1990s were simply places which hadn’t caught up yet. The bitter warfare and ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia were just the last spasms of the end of the Cold War.

Perhaps they were, but the Cold War’s legacy lived on in other conflicts occurring throughout the 1990s, and ones which led up to the new age. Events like the Gulf War, Somalia, and the genocides in Africa were such “minor events” that didn’t rate the same level of total focus the Cold War did. They were places which hadn’t caught up to the winning ideology.

Francis Fukuyama was wrong when he called the fall of communism “The End of History.” The hopefulness and optimism held throughout the West in the 1990s would come crashing down the moment the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City did on September 11th, 2001. History didn’t end when the Cold War did.

The Global War on Terror and all its related horrors was a bright and optimistic decade away.

Leave a comment